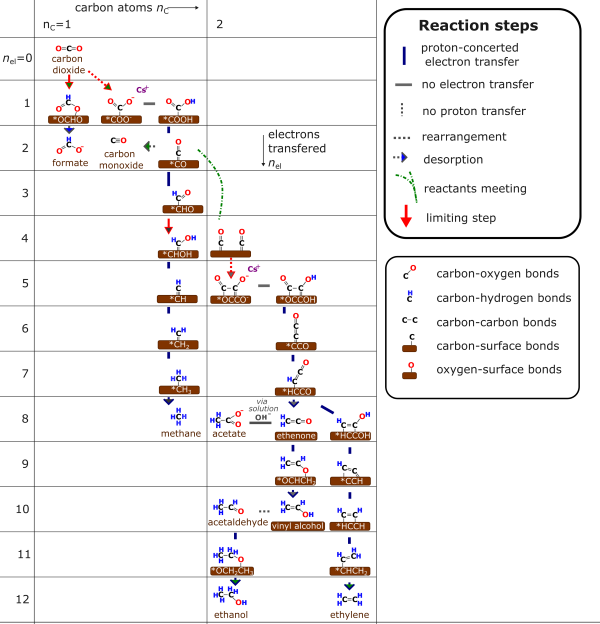

While it appears that the mechanism for CO2

electrolysis is becoming well established

(See

Figure to the right

Seger et al. ACS Energy Letters, 2025), we are now realizing that the

microenvironment has a substantial effect on the

branching points of these products. The most notable

issue for the microenvironment is to ensure

efficient mass transfer of CO2

since

otherwise the electrolyzer will produce low value

hydrogen. Gas diffusion layers allow for us to

resolve this, though there still is optimizations

needed to maxmize current density. (See

Figure to the right

Seger et al. ACS Energy Letters, 2025), we are now realizing that the

microenvironment has a substantial effect on the

branching points of these products. The most notable

issue for the microenvironment is to ensure

efficient mass transfer of CO2

since

otherwise the electrolyzer will produce low value

hydrogen. Gas diffusion layers allow for us to

resolve this, though there still is optimizations

needed to maxmize current density.As the mechanism on the right demonstrates, all highly reduced products proceed through a CO intermediate. While species like Au and Ag bind this too weakly and most other metals bind this too strongly, Cu is unique in that is binds this moderartely. Thus the CO is bound weakly enough to move around on the surface, but strongly enough not to come off. This typically allows for further reduction of CO to products such as ethanol and ethylene. While this is valid at room temperature and pressure, increasing the pressure will result in stronger binding, less reactive CO whereas higher temperatures will give the CO more energy allowing it to more easily leave the surface of the catlayst. Academic research has typically focused on room temperature CO2 electrolyis as this is simple experimentally, however any commercial device will have heat build-up resulting in a minimum of 60-80 °C for the electrolyzer. Commercially any incoming CO2 will come from a pressurized source and the gaseous products will need to be pressurized for storing or transportation. While the water electrolysis industry often pressurized their gas after the electrolyzer, there is an increasing drive towards pressurized water electrolyzers. Whether commercial CO2 electrolyzers will be pressurized is an open question. One interesting result that we have already found is that increasing the temperature just to 60 °C results in a notable weakening of the Cu-CO binding strength resulting in a higher CO selectivity. Fortunately CO is the rate determining step for CO2 electrolysis, and this results in the equilibrium surface coverage of the catalyst to be primarily covered with CO. Since we can measure CO with infrared spectroscopy (specifically ATR-SEIRAS), we can analyze how CO behaves as we vary the temperature. As expected, we saw that the surface coverage of CO decreases substantially around 60C. This study can be found in the work by Giron-Rodriguez et al., EES Catalysis, 2024. This work has spurred on further work in our group as we look at temperature and pressure variations in terms of the product distribution that we produce. |

||||

|

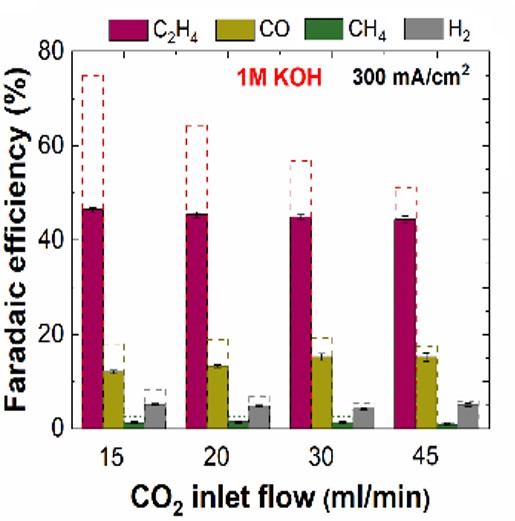

Environmental issues relating to device

engineering The rate limiting step for CO2 electrolysis is either the first electron transfer into CO2 (for Ag, Au, Sn...) or for Cu, the coupling of 2 CO's to form an OCCO intermediate. In neither of these cases is a proton involved, whereas in the competing water electrolysis to H2 gas, a proton is involved in the rate limiting step. Because of this, operating more alkaline favors CO2 electrolysis products versus low value H2 evolution. The obvious solution would then be to go to as high a pH as possible. However highly alkaline conditions (think high KOH- concentration) reacts with CO2 to form either HCO3- or if it is very alkaline CO32-. This effectively buffers the maximum pH one can operate to the pH of CO32-, which is around pH =12. This causes 2 major issues. Issue #1 The first issue that many researchers tried operating in KOH (i.e. alkaline solutions) thinking that they could react the CO2 before it would interact with the KOH. To do this they would use a gas diffusion layer approach, which is the same optimized engineering design approach that fuel cells and the chloro-alkali industry uses. A practical issue is that any CO2 that was reacted with KOH to form solubilized K2CO3 would decrease the outgoing gas flow rate. This in itself is not a major issue, but the main method to detect gaseous products (gas chromatograph) only detects concentration rath

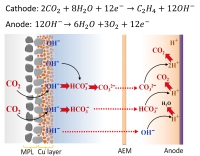

Why did researchers do something so stupid? It should be obvious to anybody that if you need to measure the products of a reaction, you should do the measurements after the reactor rather than before. So why did people use the inlet flow rate rather than the outlet flow rate for measuring their products? The gas flow rate going into the reactor is a variably that can effect the reaction, so all decent researchers have mass flow controllers to control the gas flow rate going into the reactor. In the early days of this field, CO2 electrolysis was done at a fundamental scale meaning low conversion rates and beaker type cells (e.g. H-cells). The low conversion rates meant that inlet and outlet were pretty much the same flow rate. Furthermore people would not even try to put KOH with CO2 because they knew that this would react to form carbonates. It was only when people started using the more complex gas diffusion layers was this concept of KOH with CO2 even conceivably possible. This explains the historical backing behind why researchers just used the inlet flow rates, but why not just put an extra mass/volume flow meter after the reactor? This is actually not as simple as it sounds. Most mass/volume flow meters are based on thermal conductivity or gas viscosity, and the reactor outlet is a mixture of many gases, which are constantly changing depending upon the reactor operating conditions. Thus calibrating a mass/volume flow meter fow all these gases is quite challenging. The biggest challenge is that hydrogen, which is a major unwanted byproduct, has a significantly different thermal conductivity and viscosity compared to CO2 electrolysis. Another problem with these meters is that the market is small. For industrial sized mass and volume meters there are significant options, but for research sized flow rates, the options are limited. We went with either a buyoancy (not that accurate) or a physical displacement device (breaks often). However a simpler way is just to bleed in a small known rate of an inert gas (either before or after the reactor) and then see how much this gas gets upconcentrated or dilluted by the time it gets into the gas chromatograph. From this one can then calculate the outlet flowrate of the reactor. The length of this paragraph should help explain why researchers used inlet gas flow rates even though it was known not to be the optimal solution. One dissapointing trait of many of these works that presented high CO2 electrolysis selectivities to gases (primarily ethylene) is that they never measured all the products to achieve 100% Faradaic efficiency. Since Faradaic Efficiency is just an accounting of where all your electrons went, if this does not add up to 100%, something is probably wrong. Some of the early works slipped around this issue in denoting that they were only measuring gas products as liquid products need to be measured another way. Granted that unlike gas products, there are no commercially available in-situ approaches to monitoring liquid products, so this is a bit more complex. Still, this is not too complicated to do ex-situ by taking aliquots from the liquid electrolyte. If researchers would have done this gas+liquid product analysis, they would have realized their errors. However by not realizing there errors, they ended up getting high impact papers with lots of citations that has boosted their careers. Where is the field now? This is really a great field of researchers in that once this issue became apparent everybody started measuring their outlet flow rates. The field switched quite rapidly and by 2022 almost everybody was measuring gas selectivities properly. This is why you may see a research group have outstanding ethylene selectivities in 2019-2020, but then a couple years later the same group is having much lower selectivities towards ethylene. I think this is just something that happens in fast moving fields like CO2 electrolysis in that you have mistakes, but then you correct them and move on. Still, every once in a while a paper will sneak through reviewers with ultra-high ethylene selectivities. If you see one of these, check to see if they are operating in highly alkaline and how they are measuring their outlet flow rates. It is an easy way to catch wrong papers. Where are we going with this focus moving forward? As complex as CO2 electrolyzers, monitoring where things are going is always interesting. Anytime we produce a new product, such as those mentioned in our New Electrochemcial Synthesis section, we can reanalyze everything that is going on. We have a good understanding of the carbon balance, however we would also like to do something similar with water and humidity. Some work has already been done in this field, but I feel there is more to look at here. Especially when we start modifying the temperature and pressure, there will be a lot of new science to discover. Issue #2 While the first issue related to errant measuring techniques that are easily resolvable, the second issue is much more substantial. The second issue is understanding where all these carbonate species go. Since is essential that we 1) operate in an alkaline environment to prevent hydrogen evolution, and 2) have alkali metal cations to speed up catalysis (see here for why), this favors using anion exchange membranes, as this can keep a relatively alkaline environment and allow some, but not too many cations to reach the cathode (otherwise the cations will form salt deposits). Ion exchange membranes are needed to prevent product crossover, but still allow for charges to balance out. Analyzing anion exchange membranes For the case of water electrolysis: At the anode we pull electrons from H2O resulting in O2 and H+. At the cathode we take these electrons add energy to them and then use them to produce H2 and OH-.

Now, look at the case of CO2 electrolysis as shown on the left. The anode reaction is quite similar and the cathode simply replaces H2 with ethylene (i.e. C2H4). However, as noted previously, the OH- on the cathode reacts with CO2 to form CO32-. This CO32- goes throught the anion exchange membrane rather than the OH- . Being larger and more negatively charged it does not flow through as easily, thus resulting in a higher ohmic loss getting this accross the membrane resulting in a a reduced energy efficiency. That is not the biggest problem though. Once the carbonate reaches the anode it interacts with the H+. Since alkaline pH absorbs CO2 to form CO32-, then the acidic conditions from the H+ entails CO32- is converted back to CO2,which is then released on the anode. In theory there is nothing wrong with CO2 coming out the anode. However O2 is also being produced at the anode, thus our anode is producing a mixture of CO and O2.... just like an internal combustion car. This is not good! If you do the math, for CO2 to ethylene, 2 CO2's produce 1 ethylene, but in the process 6 CO2's travel to the anode combining with 3 oxygens to provide an anode outlet that has more CO2 than O2 in it. Of course you can separate the CO2 and O2, but that is expensive and the entire point of CO2 electrolysis is to be a process that helps eliminate CO2 from the atmosphere/oxygen. Many researchers, ourselves included are trying to get around this issue, but nothing has been shown that effective. However there is one clear workaround. CO Electrolysis The major engineering issue with CO2 electrolysis is that it reacts with water to form carbonates. Given that we need water to provide the hydrogen for making hydro-carbons, we can not get around that. However if we revert back to the mechanism for CO2 electrolysis, we will note that CO is one of the first intermediates and CO is a stable molecule. Thus CO electrolysis operates very similar to CO2 electrolysis, except that CO does not interact with water to form carbonates. Not only does this mean that we will have no CO2 or CO coming out our anode, this also means that the much more conductive OH- will be going through our membranes thus increasing energy efficiency. Furthermore ,since there are no carbonates to buffer the pH we can operate in more alkaline conditions, thus mitigating unwanted H2 production. Thus CO electrolysis seems like the perfect way to do electrolysis.... if only we can get another approach to get us from CO2 to CO. Solid Oxide Electrolyzers operate at 600-700 °C and are being upscaled on the megawatt and soon to be gigawatt scale by Topsoe for water electrolysis. While Topsoe's first market is hydrogen due to the simplicity of the product, these devices are also extremely efficient at electrolyzing CO2 to CO . As these devices need to operate at these high temperatures to ensure conductivity of the solid oxide, it is basically impossible to form carbon-carbon bonds at these temperatures. Thus solid oxide electrolyzers are great at going from CO2 to CO, but can not go any further. They are a perfect match for low temperature (~50-80 °C) CO electrolysis. Technology is rapidly changing, but from what I see currently this tandem approach of CO2 to CO followed by CO to ethylene, ethanol, acetic acid... has the largest potential. To a large extent my group focuses primarily on CO electrolysis rather than CO2 electrolysis. However the general public is fearful of CO and loves a technique that can use CO2 thus I mostly talk about my research in terms of CO2 electrolysis as it is more presentable. Honestly, how many people do you think made it this far on this webpage to understand the intracacies of why CO electrolysis is better than CO2 electrolysis? |

|

Environmental effects |

|